I met Yu Linhan a few weeks ago during a very short trip to Berlin, where I was fortunate to be introduced to the artist’s remarkable experience, and deeply philosophical thought-process behind his work.

After receiving his BA from China Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), Yu Linhan studied at the University of the Arts Bremen, where he received his diploma and Meisterschüler (Master Student) degree in 2018.

Although Linhan was already represented by the Hive Center for Contemporary Art 蜂巢当代艺术中心 – an internationally recognized space in Beijing – he decided to stay in Germany, and moved to Berlin shortly after graduating from Bremen.

From a young age, Linhan enjoyed drawing and painting.“Painting gives me a sense of achievement, a sense of existence,” he explained.

While studying painting in China, however, he felt himself gradually hitting a wall – the curriculum was very strict, with most of his energy being directed towards formalist aspects of painting, such as technique, use of color, composition… It was not until Linhan moved to Germany that he was able to set himself free from these restrictions.

The University of the Arts Bremen is known for its focus on conceptual art, with many of its professors being prominent conceptual and performance artists themselves, such as Natascha Sadr Haghighian (aka Natascha Süder Happelmann). This drastic change of environment, new form of education and the artist’s departure from pure painting left a deep impression.

Lin Han’s artistic practice has always centred on medical treatment and hospital environments – a theme that is now more relevant than ever before in light of the ongoing COVID19 pandemic. Two long hospital stays, due to a fractured vertebrae, have had a huge impact on Yu Linhan’s outlook on life. His early works, up until 2013, show scenes from hospitals, sometimes focusing on doctors and nurses, sometimes on the complex interior structures.

When Linhan moved to Bremen, he did not want to depart from painting completely, and chose a professor within the small painting department to be his advisor. This professor’s abstract painting style stood as a stark contrast to the realistic, figurative style that Linhan was used to. These two extremes ended up giving the artist a fresh new perspective. He started using block-printing and screen-printing methods. The new technique enabled him to bring a spontaneity to his painting that he felt was impossible to obtain in “pure” drawing or painting.

When printing, the artist could never fully control the outcome, which made it impossible to say how the artwork would turn out – something, which Linhan found highly interesting, and continues to explore in his current work.

On first glance, one might think that Linhan’s new body of works has departed from his early paintings entirely. On closer inspection, however, the viewer will discover that the depictions of hospital scenes and medical equipment in his early figurative paintings had, in fact, created a strong foundation, which continues to influence the artist’s current work profoundly.

What might seem like abstract symbols surrounded by expressionistic brushstrokes of monochrome color are actually screen prints of disposable medical equipment, hospital structures, wires, structures of the nervous system, gastroscopy recordings, nasal structures, and even artificial organs.

The images of medical devices in Linhan’s current works are obtained from German clinics, following some of his own examinations.

In Germany, there is a rule that disposable devices, used during medical examinations, should be given to patients afterwards to recycle on their own. Yu Linhan was able to make excellent use of this disposable equipment by recylcling it directly into his artworks.

One example is a mouthpiece, known as a spirometer, which is used to obtain accurate respiratory data by being inserted into the mouth. Fascinated by the tool’s shape and function, Linhan uses its image repetitiously as prints in many of his artworks, thus, transforming this apparatus for observing the human body into something observed.

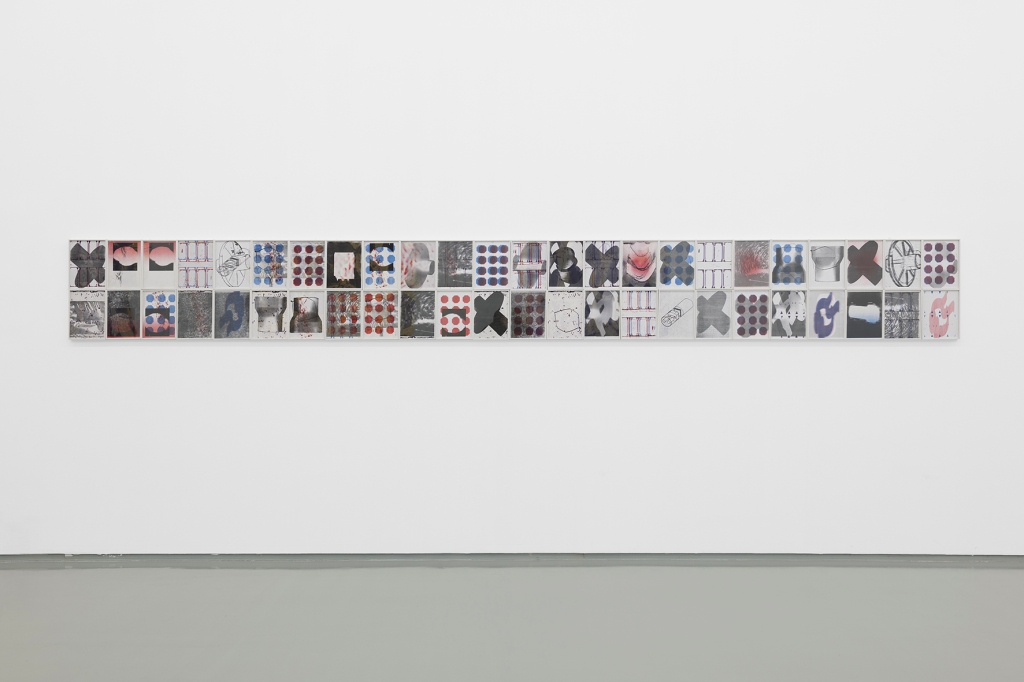

In Vivo, mixed technique, 21 x 29cm © the artist

In Vivo, mixed technique, 21 x 29cm © the artist

The spirometer images, similar to the repetitious nature of Andy Warhol prints, occur in different forms as they are printed over and over again, some only appearing as dark 2-dimensional shadows of themselves, others appearing as precise engineering-design-like models.

This reverse observation can be found in many other works. In one instance, Linhan was able to acquire gastrointestinal endoscopic image documentation. He found the photographs interesting, and integrated them into his paintings. Another image present in his works is the complex nasal structure recorded during another examination. The artist drew the structure in large format directly on the wall as a pencil drawing for his solo exhibition during the exhibition “恶是”/ The salvation of Shahrazad / Memo of the new generation painting at Hive Center for Contemporary Art.

Stemming from his own tests, these images represent a highly personal experience, but they also express the complicated relationship we all might have towards foreign objects entering our bodies during medical examination, and the mixed emotions felt towards these intrusive, yet often life-saving medical tools.

In contrast to the importance of spontaneity described in his works, Linhan chooses his colors very carefully.

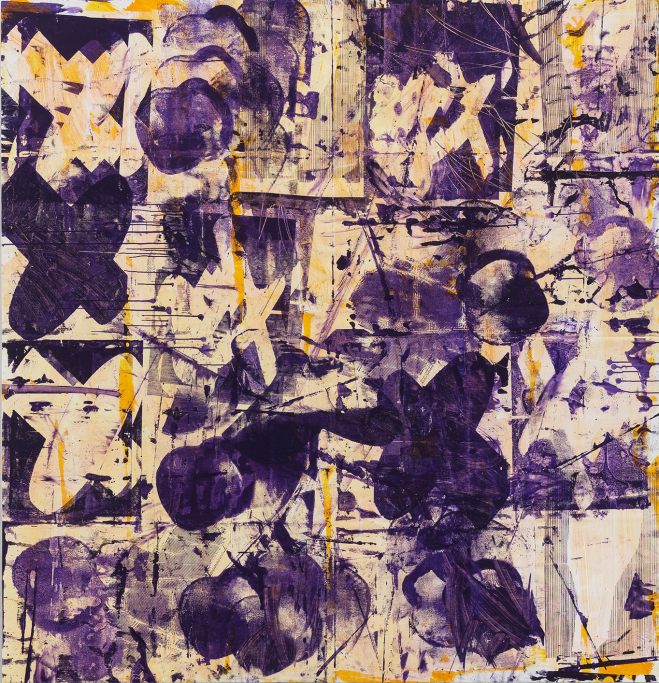

Purple is a direct reference to a popular ointment made of an herb called gentian, which was applied to the skin to treat wounds during the artist’s childhood (due to the ointment’s purple color, it is named “紫药水 ziyaoshui” in Chinese, which literally means purple medicine). Although basically obsolete today, the medicine is known to anyone who was born in the 1980s in China.

The color brown-red, in turn, references the color of a very similar (also outdated) disinfectant that was used in Germany to treat wounds (an iodine antiseptic, named “Jod” in German). The visual effect of this ointment is in both cases highly conspicuous, as it not only draws attention due to its color, but because it is applied generously and takes up a large area of the wounded skin.

Gentian Violet 2, 2019. Mixed technique, acrylic on canvas, 210 x 200 cm © the artist, courtesy Hive Center for Contemporary Art

Linhan originally used the color yellow because of its alarming effect. However, out of pure coincidence, the artist realized afterwards that the colors yellow and black are, in fact, used for the German certificate for vaccination (the “Impfpass“).

The artist uses the color blue as an association with hospital environments, for instance, the clothes that are worn by nurses and doctors, the color of face masks etc.

In his most recent series of works, Yu Linhan concentrates on his own ideas and visions of future medicine and medical technology developments. In these works, the artist integrates images of artificial organs, which is why he calls the series Leben mit fremden Organen (living with foreign organs). Linhan delves into the seemingly endless possibilities of future inventions (artificial organs just being one of them), and raises the ethical questions of humans playing god. Looking at past human errors throughout history, Linhan wonders what boundaries should be overstepped before we do more damage than good. He doubts that we will ever be able to become the gods we imagine we could be, citing an award-winning British science-fiction novel, Rendez-vous with Rama. The book recounts the first human contact with an alien spacecraft, raising questions towards the significance of human kind and our ability to take control over our existence when facing the unknown.

When asked whether his professor in Bremen changed his art making into becoming more abstract, Yu Linhan simply stated that his professor changed his mentality and his ability to make judgements more than anything else.

“Drawing is actually not a medium,” Linhan explained. “It is a mentality. For instance, a video can be like a drawing in nature, or a sculpture can be painterly in nature.” Drawing and painting, he concluded, is, therefore, incapable of dying, since it is a concept – not a medium.

There is an incredible amount of thought behind Yu Linhan’s work, and yet, it is important to the artist that the viewers do not understand his works immediately. If too much content is revealed, in his opinion, the work would become too narrative, and its artistic value would be reduced.

“Similar to when you meet a person,” he explained. “If you know right away what kind of personality he or she has, this meeting would be very boring.”

I can say for certain that, if Yu Linhan’s work were a person, it would not be the kind to wear its thoughts on its sleeves. After our first meeting, I feel I have only scratched the surface, and look forward to finding out much more.

Very interesting article; thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Thank you ❤️

LikeLike